101 things we now know about US housing markets (Part I)

Insights from the Historical Housing Prices Project: the headlines

How did the U.S. housing market perform over the twentieth century? It may come as a surprise to some but… we don’t know. Detailed information on sale prices by city only date from the 1970s while series on rents by city often date only from the 21st century (if at all).

Until now. As of June 2024, the new Historical Housing Prices Project, hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, is live. This is a project I’ve been working on for almost a decade, with my collaborators Allison Shertzer and Rowena Gray — and with financial and logistical support from the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, the National Science Foundation and the National Bureau of Economic Research as well as Trinity College Dublin, the University of Pittsburgh and UC Merced.

What? And why?

The goal starting the project was, at least in theory, relatively simple. Surely it should be possible to generate reasonably accurate indices of housing prices, both sale and rental, for major US cities for the 20th century. The fact that these didn’t exist struck me as odd, given how central housing is to modern economic life. (This is true even if you don’t subscribe to the ‘housing theory of everything’.)

OK, you say, but — as an investor might say — why now? And why you?

Over the last ten years, millions of pages of historical newspapers have been digitized, principally with genealogical goals in mind. But newspapers contain more than just records of people’s grandparents. Real estate listings were the backbone of newspaper’s golden age in the U.S. Indeed, it’s somewhat ironic that, while conventional wisdom blames Facebook and Google for eating the revenues of the major newspapers, really it was real estate listings moving online that did the damage. (If that sounds like a stretch, consider the fact that the real estate section of the LA Times in the 1990s had almost 100 pages!)

So the 2010s brought about the opportunity to excavate reams of data that lay hidden in the microfilms and microfiches of libraries around the US.

Who?! And how?

But that still doesn’t explain how I got involved. After all, I’m an economist based in Ireland. As it happens, my areas of interest are housing markets and economic history. I’ve been working in both spaces for two decades, including extensive work converting real estate listings into housing price indices, through my work with the Daft.ie Report in Ireland and in work for the IMF with a range of countries around the world. The logic carries over from online listings to newspapers listings: listings have both a measure of price but also measures of size, type and location, meaning it is possible to come with reliable measures of property price trends over time.

So, with Allison, Rowena, and a huge team — there is a literally an appendix of acknowledgements and thank yous — we gathered listings for each of thirty cities, as far back as they would go, to 1890, and up to 2006, at which point online listings start to take over. There are lots more technical details in the NBER Working Paper, joint with our co-author David Agorastos. But in brief, we built a dataset of almost three million listings for our thirty cities, which were chosen to cover as many regions and economic trajectories as possible. Controlling for housing unit size, type, and location in city from the ads, we use hedonic regressions to construct indices at the city level, at annual frequency. A “rolling windows” method helps us to minimize the challenge of unobserved changes over time, including in the quality of housing and in the price of locations.

What’s new?

Over the next few weeks, my plan is to delve into this deep database and highlight dozens of new insights. Today’s post will go through the first eight headlines, all of which are national in nature, across both sales and rental segments. The next post will look at what we know from combining both segments: the return on housing as an asset. After that, future posts will go through the various main periods and cycles in the US housing market since 1890 and pick out key new insights.

#1. The real price of a home in the US was three times higher in 2006 than in 1914

Until this HHP dataset, the best information we had on how the sale price of housing evolved in the US from 1890 was the Shiller index, first published in Bob Shiller’s book Irrational Exuberance in 2000. As we explain in our paper (and indeed as Shiller himself explained in his book), there are numerous reasons to believe there may be certain limits to this pioneering index, based on its underlying sources.

And indeed one of main findings is that there was more growth than previously thought in housing prices over the course of the twentieth century. Start-to-finish, the differences don’t seem worth noting — did prices rise 51x or 57x between 1890 and 2006 — but this hides important variation over time. In particular, the Shiller index rises considerably 1890-1914 (by 27%) whereas our new information indicates that it fell marginally (by 3%) in the same period.

This creates a significant difference for the period 1914-2006. Shiller’s index increases by a factor of 40 in that period where as the new HHP national index increases by 60x. Given consumer prices rose by 20x, this means in ‘real’ terms (i.e. adjusting for inflation; this is how I’ll use the word ‘real’ from now on in these posts), we are revising housing price growth in these nine decades substantially.

Sale prices didn’t double between WW1 and the Great Recession, they trebled, in real terms. (For those who prefer their numbers as average annual growth rates, AGRs, the new evidence says that, adjusting for inflation, housing prices rose by 1.2% per year, not by 0.8% per year. (There’s lots more to say on what happen home values but bear with me!)

#2. Rents have risen, not fallen, since 1914

On real sale prices, the previous estimates were the right ‘sign’ but the wrong size. On real rents, though, our work shows an even bigger discrepancy. There is very little annual market rental data for any city in the United States until after 2000, so everyone uses the BLS Rent of Primary Residence (RoPR) series, which is based contract rents and is used to compute the CPI.

But, as we explain in the paper, there are huge question marks about this series. As early as the late 1940s, the BLS’s own statisticians were concerned that the RoPR series was understating rental inflation but this wasn’t fully fixed until the early 1980s, when the methodology was changed. We are not the first, by any means, to state this. Crone, Nakamura and Voith — among others — have done sterling work trying to adjust rental series to get a more realistic trend.

However what we can do that others could not is bring new data. These are, of course, listed rents, not contract rents, but we believe that trends in listed rents are, when handled well, highly correlated with trends in underlying market rents. And what we find is that (nominal) rents rose by a factor of 25, not a factor of just 10, between 1914 and 2006.

The RoPR series suggests that, adjusting for inflation, rents fell by almost half between 1914 and 1948 and were largely unchanged on their 1948 level in 2006. We find, instead, that rents were about one quarter higher in 2006 than they were in 1914.

In AGR terms, real rents rose by an average of 0.2% per year over those nine decades, rather than falling each year by 0.7%, on average. This is a substantial change in our understanding of the long-run path of rents — with implications for the wider cost of living, discussed more below.

#3. The Twenties were indeed Roaring

Shiller’s index of sale prices is based on five sources spliced together. The earliest source, covering the long period 1890-1934, is an index based on a survey of homeowners conducted in 1934, by housing hall-of-famer Leo Grebler together with his coauthors Blank and Louis Winnick (also a prominent housing researcher in his day). Their survey asked homeowners what they recalled paying for their home and when they bought it, as well as what they believed their home was worth at that time.

You don’t need to be a behavioral economist to think about potential sources of bias in this set-up: from bunching in year of purchase to rounding in recalled purchase price, but also challenges in understanding the true value of a home at the height of the Great Depression as well as no correction for home improvements since purchase.

But these limitations are hard to sign — which is econo-speak for, we don’t know whether it biases things up or down. It turns out the major flaw in the survey data was not about what statisticians call the ‘first moment’ (i.e the average) but instead about the ‘second moment’, the variation in the series over time. Relative to what the HHP project reveals, the survey was simply too stable over time, resulting in a forgotten boom (and bust; more below).

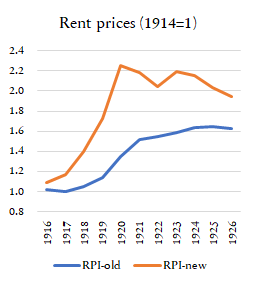

That ‘Roaring 20s’ boom can be seen in both sale and rental prices, although the timing differs. The first graph below shows the old (blue) and new (orange) rent price indices, both nominal and where 1914 is set to 1. As can be seen, market rents more than doubled between 1916 and 1920 and, while they fell back over the following six years, they remained at roughly twice their 1914 level. You can see this over and over in the rental data — both in the raw listings and in the hedonic regressions, adjusting for the mix of homes listed.

But while rents rise in the RoPR series, the increase is slower (itself not a huge concern given the different path of contract and market rents over time) and only about half as large.

The second graph show the equivalent for old and new home price indices (HPI). The survey data seems to completely miss the housing boom that followed World War 1. Part of this was immediately postwar, and so likely related to returning troops and the ‘demilitarization’ of the economy: while Shiller index (and its underlying Grebler et al component) only rises by 20% 1918-1920, the HHP series increases by 50% in the same two years.

But while market rents had peaked in 1920, sale prices were only starting their rise. They continued to rise, growing a further 25% 1920-1926 to leave them over twice their 1914 level at their peak. The Shiller index, however, shows no growth in the same six years, meaning almost all of a doubling of housing prices has been missed until now.

(For now, I’ll just note these trends. The point of these posts is to highlight new facts, with some musings on potential drivers, rather than to outline clear cause-and-effect. However, what’s worth noting across this point and the next is the classic Kindleberger bubble sequence of fundamentals → asset prices → wider economy. Rents peaked in 1920-23, sale prices in 1926 and the wider economy in 1929.)

#4. The Great Depression happened (in housing)

The Great Depression, to paraphrase Ben Bernanke, gave birth to macroeconomics. Until then, the dominant mode of thought about the economic system was that it was largely self-correcting. Since then, the dominant mode of thought has been that policy is a necessary ingredient in a healthy economy.

As Barry Eichengreen outlines eloquently in his book ‘Hall of Mirrors’, housing was at the heart of the run-up in the Roaring Twenties and thus at the heart of the crash that was the Great Depression. I’ll delve into some of the city-specific stories around these decades in later posts but what’s reassuring — especially to people like Price Fishback, who has been making this point for some time now — is that the run-up before and crash during the Great Depression is there in the HHP series. It hadn’t been so obvious before.

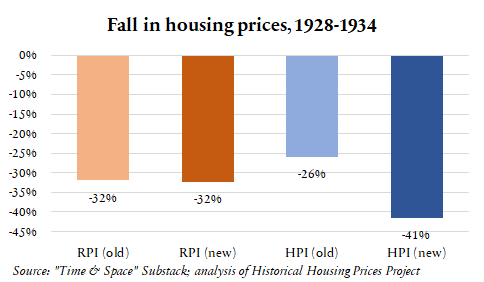

Shiller’s index does show a fall in prices, of just over 25%, but that fall only matches wider deflation in the US economy, meaning real prices in 1934 were just 1.6% lower than in at their peak in 1928. This is confusing because the RoPR series — at this point based on surveys of landlords and lettings agents — shows rents falling by about one third, i.e. by 10% more than the fall in wider prices.

I return to this below but it seems hard to believe that the yield (the annual rent as a share of the value of a home) went down, not up, during the greatest crash in US history. A bubble should be marked by yields going down — people are happy to bid more and more to buy a home, relatively to the underlying income it gives — and then the crash should be marked by yields recovering.

And that is what the HHP series shows. The fall in rents in HHP matches the fall in RoPR: nominal rents fell by a third. But sale prices fell by more than rents, not by less. In nominal terms, sale prices were over 40% lower in 1934 than they had been in 1928, at their peak. Yields went up in the Great Depression, not down; more below.

#5. The missing rent spike

The value of housing took a long time, and a World War, to recover after the Great Depression. Prices peaked in the mid-1920s at just over twice their pre-WW1 level but a decade later were just 10% above that 1914 level.

Similar to during and particular after World War 1, the Second World War saw inflation once again in all prices, including housing. Between 1941 and 1948, prices rose by at least 7% each year — and by 25% in one year alone, 1946. Overall, in these seven years, housing prices more than doubled (116%). This largely matches (although attenuates somewhat) the Shiller index, which between the mid-1930s and the mid-1950s is based on median prices from (guess what!) newspaper listings in five cities.

In the rental segment, however, the existing series — the RoPR series — implies that there was almost no growth in rents in this period. In the period 1941-1948, nominal rents in the BLS series rose by just 14%. But with the wider price level increasing by two thirds in the same period, this would mean that in real terms rents fell by nearly one third.

If true, it would mark the start of the long period of decline in real rents over four decades, until the 1980s. But the HHP series suggests that the rental sector saw an increase in prices almost as large as the sale segment did, with rents more than doubling (up 107%). We discuss in the paper that contract rents and market rents are, of course, not the same thing, but they should be going in the same direction.

Further, while there is some debate about this, researchers such as Adam Ozimek have argued market rents are also the relevant object when thinking about the cost of housing for owner-occupiers. (More below.)

If it were a one-off, perhaps you think of this as a blip. But, as per #7 below, and as per the BLS economists themselves at the time, this was the start of something more systematic. I think it is more accurate to say that real rents rose significantly — almost by as much as sale prices — during and immediately after WW2 than to say that they collapsed.

It’s also worth noting that both World Wars had similar impacts on housing markets. This is something (narrative) historians have talked about a lot but economists, economic historians and others simply haven’t had the data to see, until now.

#6. Between the mid-1950s and the mid-1970s, sale prices by half

So far we have seen, in both sale and rental segments, the HHP imply significant revisions to the path of housing prices over time, compared to what we thought we knew before. I say ‘what we knew before’ but, in line with a few of the references and links above, we are far from the first to worry that existing series are not fully accurate. (In fact, you can take our paper to be a response to these existing concerns, rather than raising them from scratch.)

But it is in the generation after World War 2 that the two most significant challenges to existing series occur. On the sales side, as Greenlees wrote in the 1980s — and as Morris Davis has written about extensively since, contrasting this measure with Census data — there are concerns about the methodology and data used to generate the sale price component of the CPI. (For more, see the paper.

What muddies the waters here is substantial inflation in the 1960s and 1970s, so we’ll focus on real measures. According to existing measure of sale prices, real sale prices were about 10% higher in 1980 than in 1950. But the HHP measure, which is not truncated and which includes controls for location, size and type, shows that prices in 1980 were over 50% higher than in 1950.

#7. Between 1965 and 1980, market rents did not fall 24%, they rose 16%

The figure above shows what happened real rents also, for the same time-span. According to the RoPR, the falling trend in rents, over time, continued after the 1940s all the way into the early 1980s, with rents in 1981 apparently just 46% of their 1914 level.

However, the HHP dataset indicates that no such fall happened in market rents. Instead, rents were largely flat (with perhaps a modest upward trend) but quite cyclical for much of the three decades after World War 2. There were five broad rental market cycles in the US between 1945 and 2006, with rents spiking in 1948 (as per above) but peaking again in 1969, 1980, 1987 and 2001.

The period 1965-1980 is perhaps a critical one when thinking about the wider implications of these revisions to our understanding of housing prices over the long 20th century. The BLS RoPR measure suggests that rents fell by one quarter in these fifteen years.

But market rents rose by 16% in the same period, according to our data and mix-adjusted methods. There are two bits of important context here. The first is that inflation (in broader consumer prices) was high throughout this period. The second is that rents often “reset” between tenancies. The method of capturing rents was based on surveying households, not dwellings, meaning a ‘non-response bias’ just at the time when rents reset to the market would systematically bias down the measure of rents over time.

The fact that our HHP rent index differs from the RoPR measure just when inflation is at its highest is consistent with those, such as Bob Gordon and Crone-Nakamura-Voith (as mentioned above), who have long argued that rents have not been falling, decade-on-decade, for a century.

#8. All this means that inflation was likely greater than previously thought

So far, we have talked about ‘real’ as well as nominal housing price indices, where we use the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to scale things so that they are comparable across long time spans. However, if the measure of housing prices is wrong, then so to is the measure of CPI.

We discuss this in the paper, in some detail. But in short, if (nominal) housing prices increased by more than we thought until now, then so too did the measure of all consumer prices — because housing/shelter is such a key component of what households spend their income on.

As of 2006, as indeed it did in 1936, housing made up one third of household spending — and going all the way back to 1890, only food came close to rivaling it. I mentioned in passing above a debate about how best to include housing costs for owner-occupiers, who are of course far more important now in the US than they would have been a century ago. Without wanting to do a disservice to that debate, I hope it’s fair to say that a measure of market rents, adjusting for the different mix of properties in the sales segment than in the rental segment, can be used to cover not just renters’ costs but also homeowners’ rent equivalent.

In the paper, we compile an alternate (indicative) revised CPI, in the spirit of Ambrose, Coulson & Yoshida’s Penn State/ACY Alternative Inflation Index for more recent periods. (Nope, the debate on how best to include housing in the CPI hasn’t gone away.) In short, we take the change in housing prices and the change in non-housing prices each year, apply their respective weights, and come up with a revised CPI.

This exercise suggests that consumer prices may have risen by an average of twenty basis points more in the existing measure for the period 1914-2006: by 3.5% per year, rather than 3.3%, on average. In aggregate, this would mean that prices rose by a factor of 24, not 20, over the long period from 1914 to 2006. The CPI cannot, by law, be retrospectively revised, because of knock-on consequences for index-linking, but economists, economic historians and market analysts may prefer this measure in future, because of its treatment of housing.

What’s next?

That’s hopefully enough for one sitting! In my next post, I’ll look at what we now know about housing as an asset and the returns to housing (both capital gains and rental yield). I hope that you enjoyed this and will come back for Part 2!